Apologies for the long gap between posts. Life has been coming at me thick and fast, and while I won’t bore you with the gory details, finding the time to finish the rather long new piece I started writing for my Substack has proved impossible.

As a stopgap, I wanted to share an interview I conducted with a literary hero of mine: Dan Fante. Fante’s “Bruno Dante” trilogy – Chump Change, Mooch, and Spitting Off Tall Buildings –changed my life when I discovered them back in the early 00s. Discovering a new writer, who was writing material that stood proudly alongside my long-dead literary heroes of Burroughs, Bukowski, Trocchi, et al, convinced me that, perhaps, there might be a market for this strange manuscript I’d been working on. When Digging the Vein was finished, I managed to track down an email address for Dan, and told him what an inspiration he was, and wondered whether he might consider taking a look at my as-yet-unpublished novel. To my amazement, he did, and came back to me with some brilliant, practical advice that I felt greatly improved Digging the Vein.

One bit of general advice he gave me that always stuck with me was this: “If you’re writing about your own life and you hit on an area that feels uncomfortable, and your first instinct is to recoil from it in horror? THAT is where you need to focus. Because THAT is where your book is.” There were several details of my own experiences that I had omitted out of a weird combination of shame and embarrassment, but when I went back and put them on the page, they became some of my favorite passages in the book. Even when they are not autobiographical, my books are rooted in my own experiences, and this is advice that has kept me in good standing throughout my entire career.

When Digging the Vein was published in 2006, it had Dan’s blurb displayed proudly on the cover: “Reading it, I could taste the LA smog. Here, pain comes at you like a Mack truck – relentless and unavoidable. Don’t blink. Keep reading.”

Years later, we would find ourselves sharing a publisher when we were both signed by Harper Perennial. Dan’s first book for Perennial was the fourth and final part of his Bruno Dante series, 86’d, which was published in 2009. I received a galley copy and tore into it, eager to see what new misadventures his marvelous literary creation, alter ego Bruno Dante, would get up to next. Midway through, I read a section that made me stop dead in my tracks. I re-read it, just to be sure it wasn’t some kind of hallucination. It wasn’t, and it read as follows:

“J.C. glanced down at the two books on the seat next to me. One novel was by Mark SaFranko and the other by Tony O’Neill. “So, you’re a reader too?”

“I am, believe it or not.”

“Who are these writers? I’m not familiar with either of them.”

“I guess you could say that O’Neill and SaFranko are part of a new wave of fiction writers. I like their stuff.”

-86’d, p.83

Incredibly, my favorite living writer had slipped in a reference to my work into his latest novel. It was a beautiful—and surreal—moment.

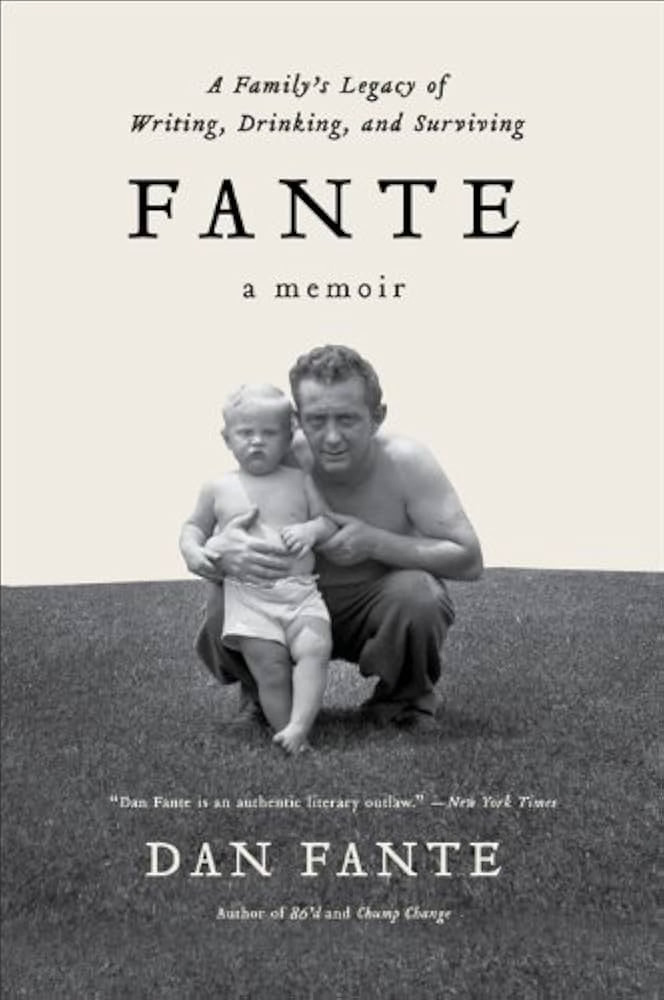

Dan’s next book was a departure from his usual gritty LA novels. It was a straightforward memoir about his troubled relationship with his father, the legendary LA writer John Fante (Ask the Dust, Wait Until Spring, Bandini, The Road to Los Angeles). It was brilliant and heartbreaking, and when the opportunity came up to interview Dan about it for the now-defunct website The Fix, I jumped at the chance.

Dan passed away in 2015. He’d reached out to me a few months prior, and I had not replied, as I was going through my own struggles with alcohol then. I had told him, and he had given me some advice, but when he wrote to me, I hadn’t acted on it and was drinking more than ever and was too embarrassed to admit it to my old friend and mentor. When I got the news that Dan had died, after a short battle with cancer, I was devastated. I went back and re-read that final email and began castigating myself for not responding. I’d love to tell you that this incident was finally able to shake me out of my stupor and I got sober, but that isn’t the case. In the short term, I dealt with Dan’s death by drinking even more. But when I finally realized I had to quit, it was Dan’s voice I heard in my head when I struggled through the rough early months of sobriety. I don’t count days, but it’s been years since I’ve had a drink, and it’s a decision I’ve never regretted. My only regret is that I never got to tell Dan that I was finally able to quit booze once and for all... but in a way, Dan is still sitting right next to me every time I sit down to write. Thank you, Dan, for the inspiration, the advice, and the friendship.

And, without further ado... here’s my piece, FANTE ON FANTE.

FANTE ON FANTE

Author Dan Fante watched his writer dad John descend into alcoholism before succumbing himself. Tony O’Neill went to Fante’s hometown of Los Angeles to talk to him about his searing new memoir, Fante, which explores his complex relationship with his literary legend father, and how alcoholism became a painful and deadly family legacy.

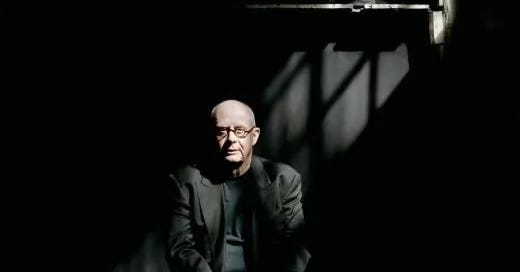

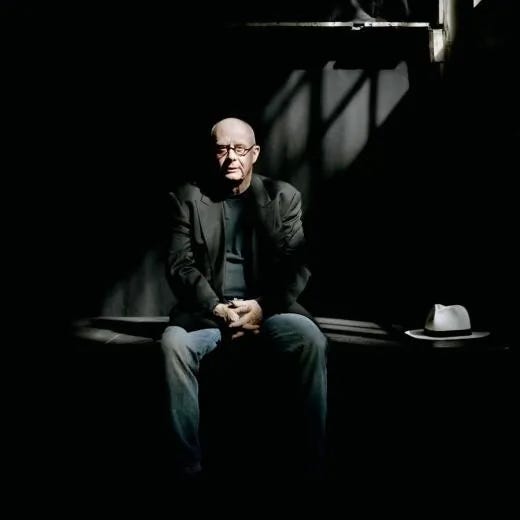

When you first meet Dan Fante, one thing you will notice immediately about him is that tattoo. It isn’t a tattoo that messes around—a world away from the hipster ink-jobs that have become trendy over the last decade or so. No, this is the kind of tattoo once sported by sailors, criminals, and those who lived outside of conventional society. It harkens back to the days when tattooing was a secretive and shady practice, and having one was a declaration of outsiderdom. The words are emblazoned across Dan’s right forearm in thick, India-ink lettering, the kind of unfussy calligraphy that can be easily read from across the room. It reads: “NICK FANTE—DEAD FROM ALCOHOL— 1-31-42 TO 2-21-91”.

Unless you are an aficionado of Dan’s work, this might be your first clue to the long shadow that alcoholism has cast over his family. Alcoholism not only blighted the life and career of Dan’s father, the legendary LA writer John Fante, whose novel Ask the Dust is rightly considered a literary classic, but also the lives of his children, Dan and Nick. Nick’s untimely death from the effects of alcohol is referenced in the ink on his brother’s forearm. Unlike his late brother, Dan was able to overcome his demons and is now coming up on 25 years sober. In his new memoir, Fante (Harper Perennial), Dan explores this generational alcoholism as well as another, slightly more benign, form of madness that runs through the Fante family tree—a ferocious love of the written word. In short, like his father before him, Dan Fante is one hell of a writer.

It took a long time for the world to catch up to the talent of the elder Fante. It wasn’t until several years after his death in 1983, that it finally became accepted wisdom that John Fante—author of (among others) Wait Until Spring, Bandini (1938), Ask the Dust (1939), and Full of Life (1952), was one of the most important literary talents in post-war America. In his lifetime, however, the pugnacious and tremendously gifted Italian-American novelist went unrecognized by the mainstream, largely due to a string of calamitous luck. After a series of well-reviewed but poorly-selling novels, Fante found himself turning to Hollywood to make a living. He drifted into a career as a Hollywood screenwriter, which earned him a great deal of money but left him creatively unsatisfied. Even though his screenplays earned him a lifestyle that many would be envious of, Fante’s stunted literary ambitions became a source of simmering frustration and resentment for a man who, to put it lightly, was known for having something of a fiery temper. In Fante, Dan recalls how his father once punched famed Hollywood director Val Lewton on the set of his 1944 movie Youth Runs Wild, after overhearing Lewton making a snide remark about John’s screenwriting abilities.

It wasn’t until the late 1970s that Fante’s reputation began to grow, thanks to the tireless championing of the poet laureate of American lowlife, Charles Bukowski. Bukowski, who once described finding a copy of Ask the Dust in the LA County library as a young man as an experience akin to “finding a lump of gold in the city dump,” talked up Fante’s work in interviews, leading to a surge of interest. Fante’s novels were brought back into print by Bukowski’s publisher, Black Sparrow Press, and the long, rocky road toward literary recognition began. Bukowski said of Ask the Dust: “Each line had its own energy and was followed by another like it. The very substance of each line gave the page a form, a feeling of something carved into it. And here, at last, was a man who was not afraid of emotion.”

There is something of a tradition of father-son authors—Kinglsey and Martin Amis, Arthur and Evelyn Waugh (and Evelyn’s sibling Alec was no slouch either), and Stephen King and Joe Hill being some of the better-known examples. But for me, there is no greater evidence of the existence of a ‘writing gene’ than the case of John and Dan Fante.

Dan Fante is the author of several important American novels—Chump Change (1998), Mooch (2001), Spitting Off Tall Buildings (2002), and 86’d (2009)—as well as volumes of poetry, a collection of short stories, and a handful of plays. Like his father, his work has not yet penetrated the mainstream—it will probably be a cold day in hell before any of his novels get an endorsement from the likes of Oprah Winfrey—but his profane and brilliant novels have spawned a fanatical and fast-growing cult. Dan’s first four novels are narrated by his literary alter ego, Bruno Dante. Bruno is Dan’s alcohol-fueled id—a raging, drunk, self-abusing, righteously angry, and yet strangely likeable resurrection of the pre-sobriety Dan Fante. These are blackly comic novels destined to shock and repel those with a faint heart, yet for intrepid readers who are willing to venture into literature’s murkier waters, they represent some of the most essential American writing of the past 25 years.

When we met at LA’s Biltmore Hotel, Dan was casually in his unbuttoned grey shirt and jeans. He is short and powerfully built and greeted me with a bear hug that knocked the wind out of me. “Back in your old stomping grounds,” he commented with a wry smile. “Hope you’ve been behaving yourself!”

I assured him that I had, and then we got down to work. Grabbing a table and ordering coffees, I began by asking Dan about Bruno Dante’s origins.

“I guess I hoped that by telling Bruno's story... I would be able to help readers identify with the madness -and sometimes humor—in his life.” Dan says. “I mean, I loved the fucked-up, out-of-control-ness of the guy. I think he's a great character.”

Dan’s new memoir, Fante, dissects his relationship with his father with unflinching honesty. Fante is an unflinching exploration of a strained yet loving father-son relationship; a tale of frustrated talent, chronic alcoholism, and eventual salvation through writing. It is, hands down, my favorite book of the year. The shadow cast by Dan’s father has always been a large part of Dan’s work—Chump Change is a fictionalized retelling of Dan’s alcoholic spiral in reaction to the news of his father’s death—but Fante is the first time that Dan has tackled the subject of his father’s legacy head on. While an excellent biography of John Fante was released in 2000 (Stephen Cooper’s Full of Life), Dan’s book is a much richer reading experience. Told from the intimate point of view of a talented but troubled son who inherited both his father’s gift for the written word and his propensity for drunkenness and bouts of rage, Fante is an often harrowing read. It is also full of pathos and heart, a book that pitilessly examines the unlucky breaks and twists of fate that frequently served to handicap John Fante’s career. For example, his best-known novel, Ask the Dust, was a critical success and was tipped to make the author a household name. However, in 1939, the book’s publisher, Stackpole Sons, published an unauthorized translation of Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf. The money that was earmarked for promoting Fante’s novel was instead frittered away fighting a lengthy, drawn-out lawsuit with none other than the Fuhrer himself. As a result, Ask the Dust sold less than 3,000 copies, and then, in the words of Dan Fante, “it went to sleep... for 40 years.”

But, according to Dan, blaming John Fante’s many career frustrations on simple bad luck would be an oversimplification.

“Look - my father's rotten luck with his books and with his film career, had a direct correlation with his uncanny ability to piss people off, “ Dan says, with a dry chuckle. “He couldn’t stop himself! If he didn't like someone—and believe me, there were plenty of folks in and out of the industry that Pop didn't like—then he would tell ‘em directly. No sugarcoating! Let’s just say, it was hardly the best way to win friends and influence people, y’know? Especially with the kind of people who often become publishers, film producers, and directors. But it never stopped him. Pop just didn’t give a fuck about the niceties. Fortunately, for my father, his incredible talent for putting words down on paper went a long way to mitigating his... unforgiving temperament.”

As detailed in Fante, John Fante was a prodigious boozer who was able to keep pace with friends who included such well-known literary boozehounds as William Saroyan (who had a long and rocky friendship with Fante) and William Faulkner. But he did not consider himself an alcoholic. “My father came from a time in America—call it the Freud-Thomas Mann-Ayn Rand period, for lack of a better term—where brilliance, education, literary sophistication, and self-propulsion were held in the highest esteem,” Dan says, with a shrug. “In that worldview, the mind was king. Artists like Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Edna St. Vincent Millay were the literary examples people followed. Drinking was all wrapped up in that mythology, you know? The artist was supposed to be quirky and volatile! So, John Fante fit right in with that paradigm. He was always a heavy drinker.”

But looking back, would Dan consider his father an alcoholic? “I’d say at times, sure... he drank alcoholically,” Dan muses. “His father was a raging alcoholic, and many of his friends were serious drinkers, and some died from booze, but I don't think my dad considered himself a drunk, as such. In his eyes, he was just another heavy drinker.”

His son, however, had no such qualms about his own drinking. As detailed in this book—and the novels that preceded it—the younger Dan Fante was a hardcore alcoholic. A “black out and wake up having stabbed yourself in the stomach with a steak knife” kind of alcoholic—a man, Fante admits, whose own brain seemed hard-wired to destroy him. In Fante, Dan explores his own darkest moments with a clear eye and wry humor, detailing his booze-sodden adventures as a carnie, a private investigator, hack cab driver, and telemarketer. Interspersed with these picaresque adventures are hard-won periods of sobriety. Describing one memorable cold-turkey detox, Fante writes:

I began to see snakes entering from under my room’s door. First one, then several. Little snakes, not big ones, but with large heads. I began opening and closing my room’s door. Slamming it shut again and again. The manager came to my room and threatened to throw me out. Finally, I locked myself in the bathroom, and the snakes gave up and went away.

While alcohol would go on to ruin John Fante’s health (he died blind, and with both legs amputated due to his severe diabetes), Dan Fante managed to get sober before his drinking killed him. The story of Dan’s recovery is told very powerfully in Fante, which offers a much more nuanced view of Alcoholics Anonymous and the struggles of sobriety than one often sees in the typical recovery memoir. One fascinating aspect of his story is how Fante admits that even after years of sobriety and regular AA meetings, he remained as miserable and suicidal as he was when he was drinking. This is something that very few authors will admit to in a culture that demands happy, neat endings.

“I see it like this,” Dan tells me when I ask him about this. “The man who’s a drunk is the furthest thing from God. But the man who gets sober without finding a way through the... madness that caused the drinking in the first place? He’s truly fucked. A pitiless wretch. That poor bastard is either going to drink again... or he’s gonna come face-to-face with death.”

So, how did Dan find his way through the madness?

“Simple. Via a vital, honest-to-God spiritual experience,” Dan says firmly. I get the impression that he’s told this story plenty in the AA meetings he attends regularly. “Thing is, it only happened to me after years and years of failed detoxes, and occasional, prolonged periods of sobriety... Again and again, I found that – despite the fact I was technically sober - I still felt miserable. Suddenly... BAM! There it is. A kind of... ZAP, only possible after intense and prolonged psychic pain. There were several months... when I was around the four-year-sober mark... where I felt suicidal. It’s what people in the rooms call ‘stark raving sober.’ I’d been taking my sobriety for granted for several years, and one day I woke up and realized my life was completely and irrevocably in the crapper.

“Tony...” he says, leaning forward and fixing those pain-filled and soulful eyes on me. “This is what it was like. I had a fucking gun in my mouth. I was ready to die – fuck no, I was desperate to die. And that is when it suddenly hit me – I wasn’t ready. Not yet. But at the same time, I couldn’t keep living like this. It was only in that moment of pain and confusion that the door finally opened, just a crack. The unbearable, psychic pain that I experienced in those early months of sobriety was a gift, I suppose... because it drove me back to my roots in recovery. I was desperate! And only people who are desperate enough to try to find God might eventually realize that there's another side to madness.”

Sobriety would crystallize something buried deep inside Fante, and he found this hard-won peace of mind had a dramatic effect on his ability to write. “It was like the floodgates were open,” Dan says. “For years, I’d been a drunk, frustrated writer. All of a sudden, I was just a writer. And I began to write every single day, just spewing out all of that old pain and despair and shame and frustration onto page after page after page. When it was done, there was Chump Change. It was almost as if I’d channeled it, somehow. That book just POURED out of me.”

In just over a decade, Dan has produced a body of work that many authors would be happy to have created throughout an entire career. Following Chump Change was Mooch, a bleak and darkly hilarious story of addiction and sexual obsession, set in the world of fly-by-night telemarketing. Spitting Off Tall Buildings was Fante’s Factotum, transplanting Bruno’s adventures to 1980s New York City, as he bounces from shitty-job to shitty-job, while maintaining a slipping grasp on sobriety. His latest book is, of course, essential reading for anyone with an interest in the work of John Fante. Fante is also one of the finest and truest memoirs to deal with themes of addiction and recovery that I have ever encountered.

As our interview wraps up, and we prepare to step out into the glaring mid-afternoon sunlight, I have one final question for Dan. Why does he think that the romance of alcohol has such a pervasive hold on literary culture?

“I’ve thought about that a lot, over the years....” Dan tells me, looking thoughtful. “The best way I can put it is just that writers, by their very nature, live internal lives, y’know? If I’m being honest... I’d say loneliness plays a huge part in many, many artists’ lives: loneliness, poverty, failed relationships... all of that stuff. I know quite a few artists - writers, painters, poets - who have to rely completely on their art to sustain themselves emotionally. Hell, that’s the way I lived for a long time, too.”

Then, Dan shakes himself out of his thoughts, shooting me a mischievous grin. “In other words, Tony... The shit comes with the territory, man. It always has.”